‘Lovely writer, lovely man:’ journalist James Deacon defined decency

His inner strength made him a top-notch editor and sportswriter—and an even better father and friend

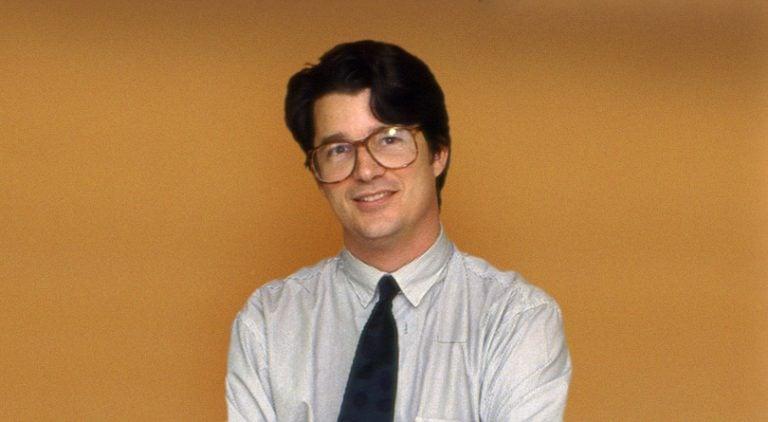

James Deacon in the Maclean’s newsroom, 1993 (Photograph by Peter Bregg)

Share

If you spent time around James Deacon, certain images come immediately to mind. There was the hair—forever flopping over his brow, untamed despite his best grooming attempts. It was so ridiculously luxuriant that it seemed to bounce into a room well before the rest of him arrived. The wardrobe was preppy before the word became commonplace. Even in winter, the mind’s eye sees him in Sperry deck shoes, corduroy pants and sweater or old blazer—or both—with, of course, a white button-down shirt underneath. He was known by either his first name or, just as fondly, a bellow of ‘Deacon’. If he was coming to see you, you learned to be patient, because first he had to have a good word with everyone in his path—cleaning staff, the receptionist, fellow journalists; all of whose family stories he knew well. And as a colleague or editor in a newsroom, you did want to see him, especially when breaking stories were happening, because as both writer and editor, he got the job done elegantly, comprehensively, and on deadline.

Jamie, who served as sportswriter, editor, sometime radio personality and jack-of-all trades at Maclean’s and the Globe and Mail for close to three decades, died last week at age 64 of complications from cancer. In a field often defined by wise-cracking cynicism, his calling cards were kindness, concern for others, and wry, self-deprecating humour. Tributes last week from colleagues reflected that. Longtime radio host Bob McCown, notable for his acerbic on-air manner during his own career, reflected that Jamie was “always a gentleman … always a friend. Never heard him utter an unkind word.” Hockey-Hall- of-Fame sportswriter Roy MacGregor remembered a “lovely writer, lovely editor, lovely man.”

READ: James Deacon’s piece on Mike Weir’s historic win at the Masters

I worked alongside him as a colleague at the magazine for more than a decade and then, in my tenure as editor-in-chief, relied on him to play a key role in any important stories—from sports to business to international conflict. Typical of his dedication, he was also a longtime board participant in the annual Michener Award organization, which honours journalist excellence in Canada.

As a sportswriter, Jamie was most interested in athletes as people rather than performers. In a 1999 Maclean’s piece on Wayne Gretzky’s retirement, he wrote: “Even while he stood in the Madison Square Garden theatre insisting his last days as a player ought to be fun, he said so with a voice that quavered, with eyes that were red and glistening, and with body language that suggested hockey’s loss was no match for the sadness Gretzky would feel when he unlaced his skates one final time.”

READ: James Deacon’s 1998 profile Larry Walker, a 2020 inductee to the Baseball Hall of Fame

Jamie shared at least one quality with Gretzky: a toughness not initially evident because of his easy-going demeanour. “He was always gentle and kind, so it took a while to realize this amazing inner strength,” recalls former Maclean’s colleague Bruce Wallace, who worked alongside him at two Olympic Games. Over the last 15 years, that was tested several ways. In 2005, he left the magazine, and, after a period as a freelance writer and radio personality, joined the Globe. About the same time, his marriage ended and he became a caregiver to his children, Eleanor and Charlie. He became a more-than-able short-order cook in his kitchen; took over the care of a cranky cat to which he was allergic and professed to dislike (but adored); managed the physical and financial upkeep of their large house, and worked whatever shifts available that were secondary to his children’s needs. As his great friend Helen Burstyn said: “Nothing came close to his devotion to his children.”

We lost a good man today. James Deacon had a rough go these past years but he was always a class act and a great writer. We covered many Olympic Games together. First as a colleague at Maclean’s then as my sports editor. Here, at the Salt Lake City games. RIP, Buddy. pic.twitter.com/wjWozmM3E0

— Ken MacQueen (@kmqyvr) January 21, 2020

Then Jamie faced a bigger crisis: a cancer diagnosis. He appeared to beat it for several years but—as would be the case for the rest of his life—it returned in various forms. Despite that, he deflected attention to focus on others’ needs. Jamie provided regular comfort to Bob Levin, his great friend and colleague at Maclean’s and the Globe, when Bob was fighting his own final battle with cancer. For a memorial service for Bob earlier this year, Jamie—by then undergoing the physically devastating late stages of experimental treatment—struggled out of bed to give a eulogy. His sole concession that day to illness was a baseball cap covering the damage to his famous hair by chemotherapy.

All of which brought to mind the tribute Jamie wrote to Maurice “Rocket” Richard on his passing in 2003. When cancer was discovered in Richard, he wrote, “the future looked bleak”—but he fought back to the point that he resumed public appearances for a while. As Jamie wrote: “Mr. Richard,” the surgeon understated, “has shown that he has an incredible strength.” He concluded the piece by writing that Richard “continued to show it—right until the end.” Jamie lived what he wrote.