How allegations of a forgery ring are threatening Norval Morrisseau’s legacy

A trial revealed an alleged wellspring of hundreds of fake paintings purported to be the work of the famed Anishinaabe artist

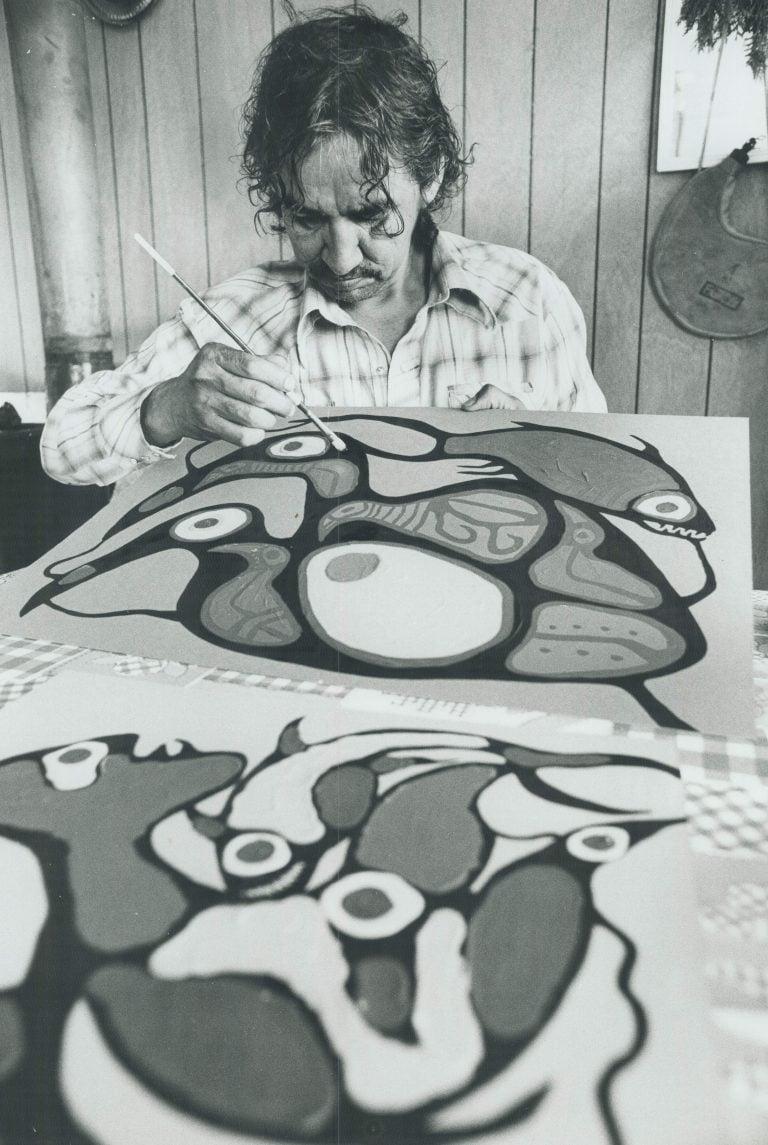

Norval Morrisseau. (Graham Bezant/Toronto Star/Getty Images)

Share

At first, nothing seemed amiss. Donald Robinson, a Toronto gallery owner, had heard about a country auction east of the city building a reputation among dealers as a cheap and plentiful source of paintings by famed Anishinaabe artist Norval Morrisseau. Over at least a couple of visits, Robinson scooped up more than two dozen paintings. He considered himself an astute judge of the artist’s work, since he served as Morrisseau’s primary dealer.

Soon, though, he felt a creeping doubt. How could this obscure auction, filled with dusty antiques and furniture, get so many paintings from such a prominent artist? Morrisseau was remarkably prolific (5,000 works is a conservative estimate), and it was said that practically everyone in northern Ontario, where he lived for much of his life, had one stashed away. Even so, many of the paintings at this auction were dated in the 1970s, a coveted period for Morrisseau’s work. Robinson found some of the details of the paintings unusual, even unsettling. Animals depicted on the canvases had sharp, menacing teeth. He took a few photographs and sent them to Morrisseau, then living in B.C., who returned a typed letter. “I did not paint the attached 23 acrylics on canvas,” it read, with a scrawled signature at the bottom.

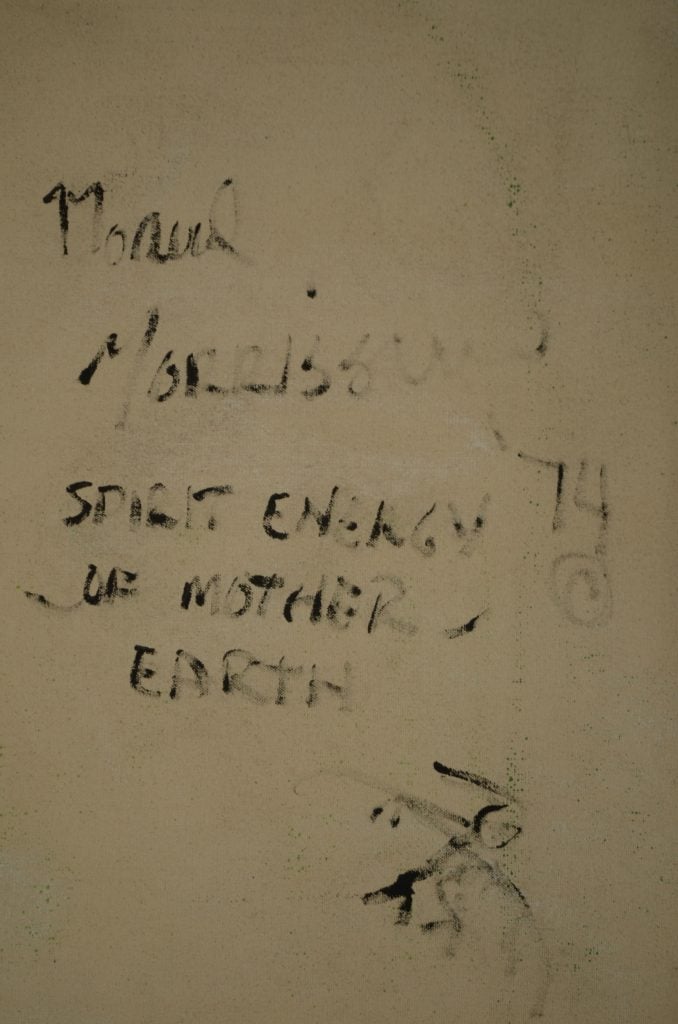

That letter was sent in 2001. Since then, some of Morrisseau’s closest associates have warned about scores of forgeries contaminating the market, tainting the legacy of one of the country’s most important and influential artists. Morrisseau was a rare talent, one who is credited with an entirely new style and who pushed the rest of Canada to recognize the value of Indigenous art. He signed the name Copper Thunderbird, given to him in a healing ceremony, in Cree syllabics on the front of his canvases. There are paintings that also bear a faded signature in English, along with a title and a date, rendered in black paint on the reverse side. (They’re referred to as “black dry brush” paintings, owing to the signature style.) Some say Morrisseau never signed that way, and that it’s likely the hallmark of a forger.

Last December, during a trial before the Superior Court of Ontario, an alleged wellspring of hundreds of fake Morrisseau paintings was finally brought to light. Kevin Hearn, best known as the keyboard player for the Barenaked Ladies, sued a gallery in 2012 that sold him a Morrisseau titled Spirit Energy of Mother Earth after he came to believe it was a forgery. The gallery owner died months before the trial, but Hearn pressed on. He’s spent much more on legal fees than the $20,000 he paid for the painting (Hearn is suing for $95,000 in total). More important to him is exposing what he alleges is the dark truth behind the painting—that it traces back to a fraud ring in Thunder Bay, Ont., masterminded by someone who knew the late artist and recruited members of Morrisseau’s family. “I learned things that were very disturbing,” Hearn said in court. “People who had been seriously hurt in this environment where these paintings were made.” He continued, “I saw things I couldn’t turn back from. As much as this is about one painting, I had to do the right thing.”

Story continues below.

None of the allegations has been proven, and a ruling in the case is pending. If true, the story told by multiple witnesses in court could cast a shadow on scores of Morrisseau paintings hanging in homes and private collections.

Born in 1931 in the Sand Point reserve near Beardmore, Ont., Morrisseau was sent at the age of six to a residential school, where, like many of his generation, he suffered emotional and sexual abuse. Later, he was drawn to his elders, and turned their oral tales into art, setting on canvas aspects of Anishinaabe culture the residential school system attempted to erase from him. The themes he explored are broad, including race, gender and colonialism.

He’s credited with establishing an entire movement, now called the Woodland School, characterized by thick black lines, vivid colours and spiritual themes. Morrisseau sometimes rendered people and animals as if captured by an X-ray machine—blown wide open, with nothing to hide. A tall, slender man with brooding eyes, Morrisseau was known to sell and trade his work door-to-door before a 1962 show in Toronto brought him national acclaim. Press coverage fixated on his personal life, particularly his alcoholism, much to his frustration. “They speak of this tortured man,” he once said. “I’m not tortured. I’ve had a marvellous time.” After a period of sobriety, Morrisseau started drinking and briefly lived on the streets of Vancouver in the 1980s.

One of his masterpieces is a sprawling 1983 work called Androgyny, offered as a gift to Canada in a letter to prime minister Pierre Trudeau. Some have interpreted the painting as a petition for the government to pursue reconciliation. It hung in the headquarters of what’s now Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada, uncelebrated for years before it was featured in a 2006 retrospective at the National Gallery of Canada, the first for a contemporary Indigenous artist. Morrisseau attended in a wheelchair, having been diagnosed with Parkinson’s in the 1990s. As his body failed, he lost the ability to paint. He died in 2007.

The painting at the centre of Hearn’s lawsuit, Spirit Energy of Mother Earth, is typical of Morrisseau in some ways. Birds, fish and other beings are set against a murky green backdrop, tethered to one another with heavy black lines. These lines are typical of Morrisseau, illustrating his belief that everything in nature is connected. In Spirit Energy, though, not everything joins together. Some lines wander off the canvas. On the back is Morrisseau’s signature in English, along with the title and the date, 1974.

Story continues below.

If you talk to Randy Potter, there’s no mystery to the painting’s origins, since he remembers selling it. Potter ran the auction that raised Donald Robinson’s suspicions back in 2001. A former autoworker turned auctioneer, Potter mostly sold antiques until a man pulled up one day with eight Morrisseau paintings in the trunk of his car. “I didn’t know who Norval Morrisseau was,” Potter says in an interview, though he recalled hearing the name. The man introduced himself as David Voss and said the paintings came from a collector in northwestern Ontario, who had hundreds stored in a shed. Potter sold them, and Voss supplied many more over the years. By the time he shut down in 2009, he had sold up to 2,000 black dry brush paintings from Voss for anywhere between $800 to $35,000 each. He never asked too many questions. “I guess I never really cared,” he says, adding, “I’ve never sold a bogus painting in my life.”

At the time, Morrisseau was living in Nanaimo, B.C., in the care of Gabe Vadas. Morrisseau met Vadas in 1987, and Vadas became both an assistant and adopted son. “Norval was a father to me,” Vadas would say later in court. “I loved him more than anything in the world. And I still do.” In the final years of his life, Morrisseau signed a series of notarized declarations identifying fakes sold by a handful of galleries (including the one that sold Spirit Energy to Hearn) and Potter’s auction. Morrisseau, by then in a wheelchair, would carefully review dozens of images and only add a work to a declaration if he was certain he did not paint it. He was deeply upset by what he saw, according to Vadas, and the process was painstaking. Morrisseau’s lawyer threatened to sue a few galleries, but never did, owing to the cost to Morrisseau and his declining health: the artist was having increasing trouble moving and speaking.

After Morrisseau died, the RCMP launched an investigation to probe allegations of forgeries, but closed the file after two years in 2010. In an email obtained by Maclean’s, one officer wrote that “our investigation has uncovered evidence of fraud” and noted the RCMP sent a referral package to the Thunder Bay Police Service. No charges were laid.

Some buyers have taken their chances in civil court. Jonathan Sommer, a lawyer with no experience in art fraud at the time, was retained by a retired teacher to handle a small-claims suit against a Toronto gallery over a Morrisseau piece called Wheel of Life. The painting passed through Potter’s auction before the gallery sold it. Sommer produced Morrisseau’s sworn declarations, including one singling out Wheel of Life as fake. “There’s no reason not to believe it,” he says. “It’s coming from the artist himself.”

The defence lawyer zeroed in on Morrisseau’s mental competence when he signed the declarations, however, suggesting he was “very inconsistent in what he says is real and what he says is fake.” The gallery director claimed Morrisseau was manipulated by Vadas and Robinson to control the market for his work. (This was denied.) Morrisseau’s brother, Wolf, testified that the artist did sign his name on the back of his paintings. “In fact, I was the one who helped him to sign his English name on the back of his artwork,” Wolf said. He reasoned an English signature would make his brother’s work more recognizable around the world. Finally, a handwriting analyst determined the signature belonged to Morrisseau.

In the end, the judge called Wolf an “entirely credible witness,” found the signature analysis convincing and doubted the “reliability of Morrisseau.” The painting, the court ruled, was authentic. “It was just shocking to me,” Sommer says. He filed an unsuccessful appeal. By then, Sommer had Hearn as a client and was learning more details about an alleged forgery operation in Thunder Bay. This tale had circulated before. “No one has ever found this ring of painters up in Thunder Bay,” Potter says. “It’s just a myth.”

Dallas Thompson took the stand on the fourth day of Hearn’s trial in December 2017 and told the story of how he helped to sell fake paintings. Thompson, 32, grew up in Thunder Bay. When he was 16, he met an older man named Gary Lamont. Lamont was known as a drug dealer, and he and his common-law partner housed Indigenous students from northern reserves attending high school in the city. Lamont also kept a property north of Thunder Bay, where the house had bars on the windows and locks on the doors that required a key to open from the inside, according to court testimony.

Thompson lived there sporadically starting in 2003 and became an assistant of sorts to Lamont, who sold Morrisseau paintings. Thompson wrote emails to customers, packaged canvases, travelled with Lamont to other cities to hawk artworks and handled cash from sales, which ranged anywhere from $3,000 to $25,000 per piece. Lamont had known Morrisseau since at least the 1980s. His website featured photos of the two of them drinking tea or sprawled on their backs on top of paintings. Morrisseau, according to an archived version of the site, gave Lamont the name Spirit Chaser, an entity that can dispel evil.

Thompson wasn’t the only one living at Lamont’s property. Benjamin Morrisseau, a nephew of the famous artist, stayed there as well. He spent much of his time painting in the style of his uncle. When he finished a work, according to Thompson, Benjamin signed the back of the canvas as Norval Morrisseau in black paint and added a title and a date. Lamont’s customers never met him. “Benjamin was hush-hush,” Thompson said.

For years, Lamont paid Benjamin and Thompson for their services. For Thompson, that also meant picking up supplies, so Thompson could use his First Nations status card to get a sales tax exemption. The co-owner of one art store they frequented combed through receipts and signed an affidavit stating Lamont spent enough money on canvases to produce approximately 900 paintings. Amanda Dalby, a niece of Lamont’s partner, testified that she too had seen Benjamin paint and sign works as Norval Morrisseau. She’d even seen sheets of paper he used to practise the signature, and recalled how Benjamin and another associate spent hours trying to replicate it. She added another allegation: Wolf Morrisseau, the artist’s brother, painted for Lamont, too.

The year before Morrisseau passed away was unusually busy. “It’s crazy,” Thompson recalled in court. “Every day, all day long, I’m running back and forth, grabbing paintings, looking for them, talking to potential customers.” By then, Benjamin had moved to another town and took a train to a rural outpost north of Thunder Bay roughly every other week to offload more paintings.

The pair soon fell out. “Gary stopped paying Benji, and Benji told him, ‘When the money stops, the brush stops,’ ” Thompson testified. Lamont found someone else. Sometime in 2006 or 2007, Lamont told Timothy Tait, an Indigenous painter in Thunder Bay, that he liked his work and offered to trade him cash and marijuana. Tait agreed, according to an affidavit entered during the trial. Lamont sometimes told him what to paint and which colours to use, and instructed him not to sign any of the works. A few months later, Tait was trying to sell some of his paintings downtown when he noticed a flyer featuring a photo of a work he’d done for Lamont. On the front was Morrisseau’s Cree syllabic signature. Tait suddenly felt used. His affidavit includes images of 27 paintings he says he made for Lamont, all of which bear Morrisseau’s Cree name, put there by someone else.

Thompson testified that in 2006 or 2007, three people flew in from Toronto and showed up at Lamont’s, saying they were from Randy Potter Auctions. They spent $126,000 for around 30 paintings. Thompson helped count each bill at the kitchen table before storing the cash in a safe hidden in the living room. Lamont talked about other customers, too, including Voss, who supplied Potter with nearly 2,000 paintings over the years.

Potter says he never bought paintings from Lamont, nor did he visit him in Thunder Bay; they spoke on the phone occasionally, but that was it. His paintings came from Voss, he tells Maclean’s, adding he’s frustrated that Voss won’t publicly vouch for the authenticity of the works. “He doesn’t want to get involved to help,” he says. Voss wasn’t exactly forthcoming when reached by phone. “You want a comment?” he said. “Go fuck yourself.” Then he hung up.

Wolf, now 64, laughs off the allegation that he was involved in a forgery ring. “It’s a falsehood, obviously,” he says when reached for comment. As for Benjamin, Wolf doubts he was forging paintings. “I’ve never seen him do my brother’s work,” he says. “If you look at his work, it’s different than my brother’s.” Benjamin himself couldn’t be found for comment. Wolf said he didn’t know how to reach him, and nearly a dozen other family members and associates reached by phone or through Facebook either didn’t respond or said they didn’t know where he is.

For Thompson, being around Lamont became a nightmare. In 2004, Thompson was raped by Lamont on more than one occasion, he said in court. He fled to Vancouver, but came back to Thunder Bay. With no job, he drank heavily and drifted through the city. “I told nobody at that time what happened to me,” he said. “I was ashamed.” Lamont, he testified, had threatened to kill him.

One night, he found himself back at Lamont’s place, looking for drugs. He ended up moving back in. “I can’t really explain why,” he said. “I just had no place to go.” Lamont sexually assaulted him again, he told the court. In 2007, Thompson left for good. “I just couldn’t take it anymore. I felt like I was losing my mind,” he said.

Thompson only told his story years later to Mark Anthony Jacobson, a First Nations painter originally from northwestern Ontario who knew Morrisseau, and who encouraged Thompson to speak to police in 2010. Thompson told them everything about Lamont. Six to eight months passed before anyone from the Thunder Bay Police Service followed up with him. By that point, he didn’t want to talk further. “It took them so long to get back to me about anything, I just had no faith in them,” he said. It wasn’t until 2012 that Thompson spoke to police again. (Jacobson also connected him with Sommer.)

Lamont was arrested in December 2013, and was later charged with a range of offences, including sexual assault and uttering threats. By the time of his preliminary inquiry in 2015, multiple complainants were alleging he violated them. Lamont took a plea deal the following year and was sentenced on five counts of sexual assault against five men, described by the judge as “young, vulnerable victims.” Lamont, then 54, received five years in prison. “I hope everybody, the victims, can move on from this,” he said at his sentencing hearing. (He declined interview requests sent through Correctional Service Canada.)

Thompson has spent years healing and is now raising a family in Thunder Bay. In court, Sommer asked him why he was willing to testify and implicate himself in a forgery operation. “I can’t stand what these paintings represent: all the rapes and sexual assaults that took place while these were being made in the house,” Thompson said. “He’s raping my culture for profit.”

The forgery trial began on Dec. 4, the 10th anniversary of Morrisseau’s death. Spirit Energy of Mother Earth was clamped gracelessly to an easel through much of it. There was no defendant. Joe McLeod, the gallery owner who sold the painting to Hearn, was well into his 80s and died months before the trial. McLeod’s lawyer filed a statement of defence previously that denied Hearn’s allegations. But the case would have proceeded undefended if not for a last-minute motion to intervene by an art dealer named Jim White. White had started collecting Morrisseau paintings in the 1990s when he heard it would be a good investment. He ended up with more than 200, mostly from Potter, but some directly from Lamont. He’s been involved in the Morrisseau forgery saga since the beginning (in a previous court case, he valued his collection at $2.5 million) and has spent more than $10,000 to have signatures analyzed. None has been found to be fake, he says.

FROM THE ARCHIVES: The ecstasy of Norval Morrisseau

After some legal wrangling, White gained standing to essentially mount a defence. Part of his motivation is financial. He still owns about 50 paintings, and says a finding that Spirit Energy is fake would damage the black dry brush market. He also stepped in for McLeod, whom he knew, and, in a way, for Morrisseau. “You destroy that market, and you destroy the artist,” he said.

On the stand, Hearn recounted purchasing the painting from McLeod, who seemed to be an expert on Morrisseau. Hearn contributed Spirit Energy to the Art Gallery of Ontario as part of a special exhibition in 2010, but it was soon taken down when its authenticity was questioned. McLeod insisted it was real and refused to offer a refund, according to Hearn. McLeod was a regular at Potter’s auction and, according to Thompson, Lamont talked about him as a customer, too. The same year he sold the painting to Hearn, McLeod published a novel about a Toronto gallery owner used as a pawn in an art forgery scheme. (The protagonist, who bears some similarity to McLeod, outwits his tormentors in the end.)

Sommer, still stinging from the loss of the previous case, had spent years preparing for this trial. McLeod had provided a provenance showing the first owner of the painting was a collector in Thunder Bay, the one Voss sourced his paintings from. Sommer obtained a statement from the collector saying he had no record of Spirit Energy, and that it was completely unfamiliar to him. The painting, dated 1974, was created on canvas. At that time, Morrisseau was living in Red Lake, Ont., where he didn’t have easy access to canvas, according to three witnesses who worked with the artist at the time. He mostly painted on kraft paper purchased from a mill in Kenora, Ont.

Carmen Robertson, a visual arts professor at the University of Regina with a specialty in Morrisseau, testified as an expert witness. Robertson kept the painting at her house for five months and produced a dense, 67-page report. Her testimony resembled a dissertation at times as she described how Morrisseau applied paint in thick layers straight from the tube to add depth. The paint on Spirit Energy is so thin the weave of the canvas can be seen. Robertson assembled a database of Morrisseau paintings from public institutions in Canada, and of 33 artworks from 1973 to 1975; only five had signatures on the back. These paintings had more in common with one another—and with Spirit Energy—than with other Morrisseau works. Robertson concluded Spirit Energy was not painted by Morrisseau.

White’s lawyer criticized Robertson’s sample size, arguing it’s just a sliver of Morrisseau’s body of work. White produced an expert of his own: Kenneth Davies, a handwriting and signature analyst from Calgary, who testified that he’s examined about 80 Morrisseaus over the years for clients. He compared high-definition photos of Spirit Energy to four other black dry brush paintings and concluded with a “reasonable degree of certainty” the signature is authentic.

Sommer countered that since Davies’s entire sample consisted of black dry brush paintings, his conclusion was unreliable. Davies scoffed: given the consistency he had seen across all of the Morrisseau signatures he’d analyzed over the years, it was inconceivable that someone else could have written them. “There are no forgers talented enough to produce that many forgeries,” he said in court. Eventually, the forger would introduce his or her own handwriting traits. “It can’t be done,” he insisted.

In all of the evidence presented at trial, there was no direct connection between Spirit Energy of Mother Earth and the forgery ring—the existence of which, it must be reiterated, no court has ruled on. Sommer knows the lines do not neatly join together. “We needed to prove our case through overwhelming circumstantial evidence to lend credence to the notion that this painting couldn’t have come from anywhere else other than the forgery ring,” he says in an interview.

In court, White’s lawyer waved off much of the testimony as hearsay, while White himself is unmoved. “We can talk about this forever, but there is no evidence,” he says in an interview. White has spent years buying and selling Morrisseau paintings, entangled in court cases about authenticity. He stood in Lamont’s house while Lamont showed off what he claimed was Morrisseau’s Order of Canada medal. Confronted with first-hand testimony of a prolific forgery ring, wouldn’t he want to at least dig further? “No,” he says.

There is a recurring element in Morrisseau’s work, seen in Spirit Energy, known as divided circles. They resemble primordial cells starting to cleave. “I divided them in half because there are two sides to everything,” Morrisseau told Maclean’s in 1979. “Good and bad, short and tall, love and hate, man and woman.” He may well have added truth and fiction. His paintings, though, had the power to illuminate the truth about ourselves, he believed. “My art reminds a lot of people of what they are,” he once said. And that is what will always underlie the judgment of any Morrisseau painting: who you are, what you know and what you’re willing to believe.