Michael Ignatieff gets it very wrong on Syria

Ignatieff’s latest writings on the Syria situation make him very difficult to take seriously

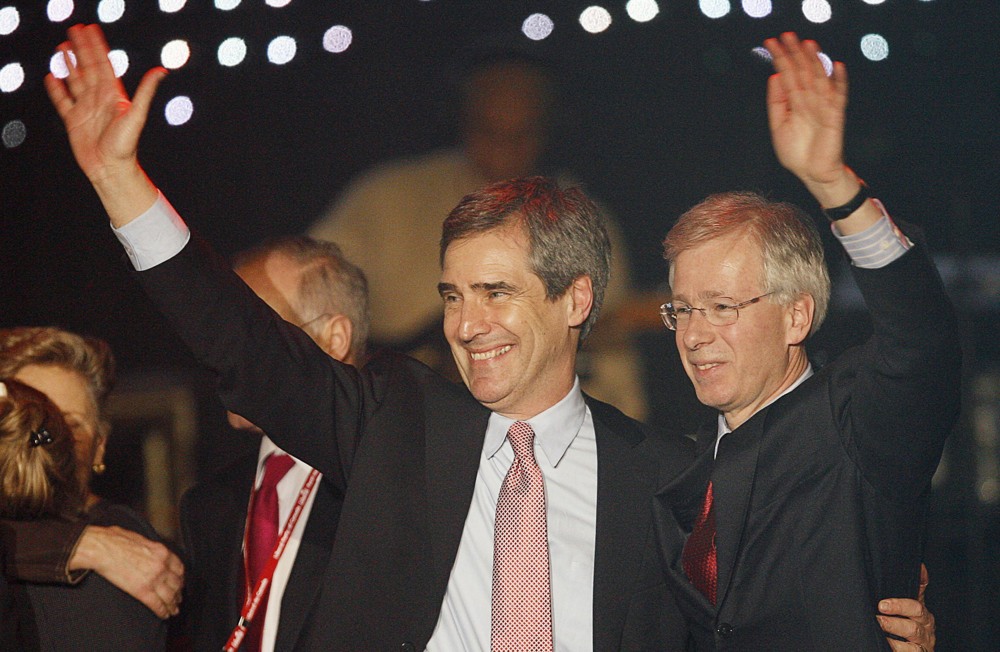

Deborah Baic/The Globe and Mail/CP

Share

Michael Ignatieff is writing again about foreign policy, which poses a challenge to those of us who would like to take him seriously, if only for old times’ sake.

The former federal Liberal leader, now back at Harvard, is certainly writing about a grave matter: the advance on the Syrian rebel stronghold of Aleppo by Bashar Al-Assad loyalists and Russian special forces. His arguments are appearing so often and in such lofty precincts—the Washington Post on Feb. 9, then in the Financial Times six days later—that he clearly wants to be noticed.

What is his argument? Well, it’s a bit of a moving target. On his first outing in the Washington Post, writing with Leon Wieseltier, Ignatieff decried “the truly incredible possibility that as the Syrian dictator and his ruthless backers close in on Aleppo, the government of the United States, in the name of the struggle against the Islamic State, will simply stand by while Russia, Assad and Iran destroy their opponents at whatever human cost.”

This policy, Ignatieff and Wieseltier add, “is shameful.” The remedy? “A perfectly realistic path that would honour our highest ideals,” they write. “Operating under a NATO umbrella, the United States could use its naval and air assets in the region to establish a no-fly zone from Aleppo to the Turkish border,” they write. That’s a swath of Syria measuring about 150 km to the north and west of Aleppo. Clearing the skies there would “prevent the continued bombardment of civilians and refugees by any party, including the Russians.”

Related: Trudeau’s ISIS policy gets an assist from Obama—and Harper

Perhaps it would also upset the Russians. On this, Ignatieff and Wieseltier were implacable. “If the Russians and Syrians sought to prevent humanitarian protection . . . they would face the military consequences.” The authors did hope that “constant contact with the Russian leadership” could avert “a great-power confrontation.” Another word for great-power confrontation is war between the world’s two largest nuclear-armed military powers. Oh well: “Risk is no excuse for doing nothing.”

This sort of talk is often hailed as “muscular” at Harvard, where Ignatieff is the Edward R. Murrow Professor of Practice, and the Brookings Institution, where Wieseltier is the Isaiah Berlin Senior Fellow in Culture and Policy. So muscular that by this week Ignatieff, writing alone in the Financial Times, was toning it down. He rhetorically downgraded the no-fly zone to an “aerial protection zone,” a distinction with no difference I can find. More significantly, he now said clearing the skies over northwestern Syria would be a “final resort.” Further economic sanctions on Moscow could come first, followed by “rapid” supply of anti-aircraft and anti-missile equipment to “trusted” rebel forces.

One spots difficulties with this chain of argument, even as amended. Two years of harsh sanctions, along with the coincidental but happy collapse in world oil prices, has not noticeably cramped Vladimir Putin’s style. A week of harsher sanctions wouldn’t do much more. Nor is it clear how rapid the deployment of Patriot or shoulder-launched missiles could be. What is clear is that such munitions rarely stay in trusted hands for long, whether because the weapons prove slippery or the trust is misplaced. So soon enough, Ignatieff’s modified argument defaults to his first: Force the air forces of Russia and Syria from the Syrian skies.

“The risks of accident, miscalculation or escalation are not small,” Ignatieff admits. But they are “justified because the stakes are nothing less than the credibility of the NATO alliance, the survival of Europe as a union and the lives of hundreds of thousands of innocent people.”

So damn the cost, he is saying. Except he also claims there wouldn’t be much cost. The likelihood of escalation (recall that this is a euphemism for war with Russia) “can be reduced” by “hourly contact with the Russian military to manage ‘deconfliction.’ ”

Here I’m afraid I move from skepticism to dismay. The cause is this word “deconfliction.” Despite appearances, it has a plain meaning. The Guardian newspaper says it describes “attempts to ensure that U.S. and Russian air forces don’t shoot at each other while they conduct overlapping air campaigns.” The Guardian first offered a definition for deconfliction in 1991: “trying not to have so many planes in the air that they collide.”

Deconfliction, in other words, means constant coordination between two or more air forces whose goals are not identical but whose motives are not overtly antagonistic. While they continue to fly in the same airspace. To avoid combat no side wants.

Which is to say that in the context of a no-fly zone enforced by one side over the others, with the stated goal of making the others face “military consequences” if they launch their aircraft, deconfliction is a perfectly meaningless word. It is a word you must not use if your goal is to convey meaning. Its use betrays the absence of meaning. It actually sucks meaning out of the rest of the sentence in which it appears.

This is where it becomes very difficult to discuss Ignatieff as though he were a serious person: Because he has already warned people not to do that when he is writing as a Harvard academic.

In 2003, at the apex of the Bush administration’s hubris between the apparent easy win in Afghanistan and the prospect of an easy win in Iraq, Ignatieff wrote in the New York Times about how awesome the American empire was. Those are his own words: “What word but ‘empire’ describes the awesome thing that America is becoming?”

This was Ignatieff’s justification for invading Iraq. At the time he had plenty of company. “Timidity is not prudence,” he wrote. “It is a confession of weakness.”

Four years later, when Iraq had turned out badly and Ignatieff had become a Liberal MP, he had a different sort of confession to make. This was his famous “Getting Iraq wrong” article, also in the New York Times. He had to explain, not only that he had been wrong to urge war in Iraq, but how such wrongness had been possible. He decided to disown his past life, on the apparent assumption that he would not return to it.

Politicians, he wrote, “can’t afford the luxury of entertaining ideas that are merely interesting. They have to work with the small number of ideas that happen to be true and the even smaller number that happen to be applicable to real life. In academic life, false ideas are merely false and useless ones can be fun to play with.”

That’s a pretty harsh indictment of academics. Was Ignatieff really saying academics could discard the true and the applicable in favour of the merely false? Well, as he wrote with a chuckle, “As a former denizen of Harvard, I’ve had to learn that a sense of reality doesn’t always flourish in elite institutions.”

Now he is the Edward R. Murrow Chair of Practice, which apparently does not make perfect. Mocking him would be pointless. And it would leave unanswered the question he at least tries to answer: What is to be done about Syria, a crossroads for many different kinds of the world’s worst people, a slaughterhouse from which millions flee?

I’m afraid I don’t know. I try to stick as closely as possible to what is true and applicable even when it is no fun to play with. I’m not sure how much a no-fly zone would help, when so much of Syria’s slaughter is happening on the ground. Even if a no-fly zone could be enforced. Even if it wouldn’t escalate to some shambolic approximation of a world war. I think Barack Obama will be haunted to his grave by doubts about how Syria got where it is. But I am sure a President Ignatieff would not be more skilled at getting it out.