Oshawa’s new mayor once saved his own life from ruin. Can he save his city next?

Dan Carter struggled with alcoholism and homelessness before turning his life around. Now the mayor of a town reeling from a major loss, he has a new challenge ahead of him.

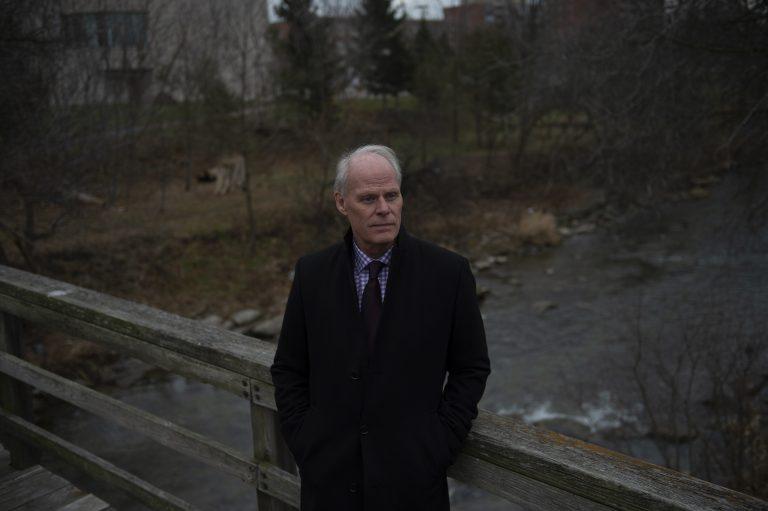

Oshawa mayor Dan Carter near his office. (Tyler Anderson)

Share

Weeks before he was sworn in as Oshawa’s new mayor, Dan Carter came face-to-face with a civic crisis that will define his term in office. In late November, rumours began to circulate that General Motors, whose assembly plant has anchored south Oshawa for decades, was about to drop a bombshell. Carter, a popular TV broadcaster who jumped into municipal politics in 2014, heard the news from a CTV reporter: the plant would close, and its 2,600 employees would be terminated by the end of 2019. (GM earlier this month rejected a last ditch union bid to keep the plant open.)

“I spent the next two days figuring out what the hell happened,” Carter says a few days before leaving for a Christmas break in Florida. He soon zeroed in on his own bottom line: “I’ve got 13 months to make sure everyone’s got a place to go to work on Jan. 1, 2020.”

Municipal politicians are always dutiful when it comes to local jobs. But Carter brings a unique sensitivity to this task. From his mid-teens to his early thirties, Carter was an alcoholic whose world deteriorated into a miasma of homelessness and despair. In June 1991, he mustered what will he had left to ask a family member for help and gradually put his fractured life back together. That painstaking process led him to a career as a local media figure and community organizer in Durham Region, the cluster east of Greater Toronto anchored by Oshawa. Those who know him well say Carter brings an almost messianic fervour to the task that lies ahead. “He’s been down,” says his friend Ken Shaw, a veteran CTV news anchor. “He understands people who’ve been at the underbelly of society.”

READ: The way we talk about opioid addiction hasn’t really changed

Carter makes no bones about any of this, nor does he attempt to disguise his religious beliefs, which date back to a lengthy stint in a Los Angeles rehab hospital and Alcoholics Anonymous. On a recent visit to his office in city hall, he has a Bible lying on the centre of his desk, opened to the Book of Job, that Old Testament parable about a man whose faith is tested in the most extreme ways. As political props go, the theatricality of all this is impossible to ignore. But Carter—a tall, engaging 58-year-old with piercing, pale-blue eyes—doesn’t come across as either a cynic or a proselytizer. “My experience, and all the things I felt, are the same things people [in Oshawa] are feeling right now.”

Carter grew up in Scarborough, adopted by foster parents as a toddler. An undiagnosed dyslexic, he struggled at school, but his troubles compounded when he was sexually assaulted at the age of eight. After his adopted brother died in a motorcycle accident, Carter, then in his early teens, began drinking. “Psychologically, [alcohol] changed who I was,” Carter says. “It absolutely destroyed me.” He dropped out of school and bounced around Toronto, eventually ending up on the street. “You’re working to feed your habit,” he says.

In 1991, he woke up one day in a rooming house and caught a glimpse of himself in a mirror, looking like “death warmed over,” as Shaw says. He called his sister, who co-owned a leasing business and had never shunned him. When she opened her door to him, she smacked him on the side of his head and told him he had two choices: sober up or die. She arranged for him to go to rehab and, when he emerged a year later, gave him gofer jobs in her company.

Not long after, Carter fell into conversation with a man who said he’d be good on TV. He started hanging out at CTV’s Scarborough studio as a volunteer before talking himself into a gig hosting a community-access show. Next came a more formal job hosting a show on a local Durham channel, CHEX TV. “I was making $75 or $100 per show, but for a guy with no education, I’m living the life, getting free suits and haircuts.” His public profile quickly took off.

Politicians soon came calling. In the late 2000s, John Tory, then head of Ontario’s Progressive Conservatives, offered him a nomination in a Durham riding, but it didn’t work out. He began broadening his reach, forging an alliance with the Embassy Church, a large evangelical congregation in Oshawa. Carter and Doug Schneider, Embassy’s pastor, co-wrote a short book about his experiences and worked on annual fundraisers. Carter also set himself up as a speaker and activist who promoted programs for the homeless and domestic violence survivors.

RELATED: GM Canada: A 100-year history of benefitting from taxpayer dollars

Shaw admits it’s unusual for Canadian public figures to mix politics and religion, but says Carter doesn’t care about denominations. “I can tell you what Dan believes,” adds Schneider. “He knows that failure is part of life. Instead of ignoring it, it’s embraced.”

Elected, finally, to Durham council in 2014, Carter turned in a respectable performance, eventually heading the finance committee. Earlier in 2018, the mayor’s seat opened up and Carter ran, winning handily.

Since the GM news broke, Carter has been working his large network of business, community, media and academic contacts. He says he’s also been fielding calls from firms poking around a potential purchase of the plant or the GM lands. That decision, of course, lies with the company, and there’s only so much a mayor can do. But Shaw says he wouldn’t be surprised to see the sprawling facility evolve into a large distribution centre. “[Carter’s] persistence could play a big part,” adds Colin James, the plant’s union leader, who wants Carter to push GM to give Oshawa a shot at building automated vehicles.

Even though the region has steadily shed auto jobs—GM’s workforce in Oshawa today is scarcely a tenth of what it was in the late 1980s—its unemployment rate is now one of the lowest in Canada. So it may be that Carter’s real job is weaning Oshawa off its historic reliance on GM’s payroll. However he formulates the region’s future, Carter has found himself thinking hard about all those GM families, and the slippery slope between pink slips and not just unemployment, but possibly addiction and even homelessness.

“This is very much like dealing with a sudden death,” he reflects. His mission—or even calling, as Schneider might say—will be to persuade his constituents that life will get better, as it did for him.